Why is ‘women’s writing’ a category? Does it have any purchase? Should it? I’ve been arguing with myself about this (again) this week.

After catching the last dramatizations of Elizabeth Jane Howard's Cazalet Chronicles on Radio 4, I’ve been looking for the books in charity shops ever since. Finding the first three books this week (The Light Years, Marking Time, Confusion) has meant that I’ve finally been able to give them a go.

Her books have been celebrated by Julian Barnes and Sybil Bedford. Martin Amis credits Howard, who was married to his father Kingsley Amis for over twenty years, with forming his literary education. But by calling her ‘the most interesting woman writer of her generation’, Amis’ praise is double-edged.

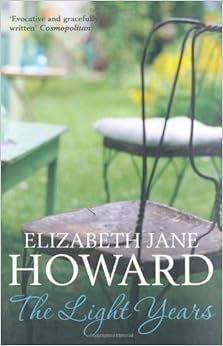

For a woman who constantly battled against being pigeon-holed as a writer only for women – and thus secondary – the books are horribly designed. No man will pick up a book with melancholy empty chairs and girly cursive and a large sticker saying ‘As heard on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour’ on the cover. (I am largely convinced that the existence of Woman’s Hour is outdated at best and, at worst, reinforces gender essentialism.)

The Cazalet Chronicles’ jacket design is a great pity, because while Howard writes domestic fiction, her work is hardly chick lit. In creating the Cazalet clan, Howard is interested in all her characters – male, female, aged, young – catching their thoughts and motivations with largely unsentimental directness. They prevaricate, evade, weaken. Admittedly, the books’ setting between 1937 and 1946 is a recipe for nostalgia along the Keep Calm & Carry On line. Still, no truly nostalgic novel so far has disclosed the answers to critical questions like What Did Women Use Before Tampons and How?

The books are unrepentantly middlebrow. The Cazalets have money and there’s an almost incredulously large number of aspiring artists for a single family. It’s the world we became familiar with in McEwan’s Atonement. If Howard’s creation is less demonic than McEwan’s, it’s because her comprehension of plot is more pedestrian. (This is not a drawback.)

The Cazalet clan centres around Home Place, the family home in Sussex, presided over by the Brig and the Duchy. Their sons Hugh and Edward, who fought in the Great War, work for the family timber firm, Rupert is a painter, and their daughter Rachel is unmarried and stays at home. We meet the wives – Sybil, Villy, Zoë – and the children. Louise wants to be an actress; Clary wants to be a writer; the boys, Simon and Teddy, are at boarding school; and the younger ones, Neville and Lydia, bring comic relief. In the second book, Marking Time, Neville and Lydia meet evacuees, one of whom warns the two to ‘Never trust a man. They’re only after one thing.’

‘One thing?’ Neville said as they trudged home later for their tea… ‘What one thing? I want to know, because when I’m grown up I suppose I’ll be after it too. And if I don’t like the sound of it, I’ll think of some other thing to go after.’

‘I can go after things just as much as you.’

‘She didn’t say ladies went after it.’

Howard’s writing is sharp, her observations of character keen, and one could argue that, while the Cazalet books are not demonstrably experimental and Howard’s writerly instincts are primarily conservative, she experiments with the range and durability of domestic fiction. If a definition of art is that which puts itself on trial, Howard may be cross-examining the genre to test whether domestic can be weighty, as it was with Austen. She is trying to dismantle the ‘Women Only’ sign that her publishers have plastered on her covers. Let’s pray she gets the chance.

After catching the last dramatizations of Elizabeth Jane Howard's Cazalet Chronicles on Radio 4, I’ve been looking for the books in charity shops ever since. Finding the first three books this week (The Light Years, Marking Time, Confusion) has meant that I’ve finally been able to give them a go.

Her books have been celebrated by Julian Barnes and Sybil Bedford. Martin Amis credits Howard, who was married to his father Kingsley Amis for over twenty years, with forming his literary education. But by calling her ‘the most interesting woman writer of her generation’, Amis’ praise is double-edged.

For a woman who constantly battled against being pigeon-holed as a writer only for women – and thus secondary – the books are horribly designed. No man will pick up a book with melancholy empty chairs and girly cursive and a large sticker saying ‘As heard on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour’ on the cover. (I am largely convinced that the existence of Woman’s Hour is outdated at best and, at worst, reinforces gender essentialism.)

The Cazalet Chronicles’ jacket design is a great pity, because while Howard writes domestic fiction, her work is hardly chick lit. In creating the Cazalet clan, Howard is interested in all her characters – male, female, aged, young – catching their thoughts and motivations with largely unsentimental directness. They prevaricate, evade, weaken. Admittedly, the books’ setting between 1937 and 1946 is a recipe for nostalgia along the Keep Calm & Carry On line. Still, no truly nostalgic novel so far has disclosed the answers to critical questions like What Did Women Use Before Tampons and How?

The books are unrepentantly middlebrow. The Cazalets have money and there’s an almost incredulously large number of aspiring artists for a single family. It’s the world we became familiar with in McEwan’s Atonement. If Howard’s creation is less demonic than McEwan’s, it’s because her comprehension of plot is more pedestrian. (This is not a drawback.)

The Cazalet clan centres around Home Place, the family home in Sussex, presided over by the Brig and the Duchy. Their sons Hugh and Edward, who fought in the Great War, work for the family timber firm, Rupert is a painter, and their daughter Rachel is unmarried and stays at home. We meet the wives – Sybil, Villy, Zoë – and the children. Louise wants to be an actress; Clary wants to be a writer; the boys, Simon and Teddy, are at boarding school; and the younger ones, Neville and Lydia, bring comic relief. In the second book, Marking Time, Neville and Lydia meet evacuees, one of whom warns the two to ‘Never trust a man. They’re only after one thing.’

‘One thing?’ Neville said as they trudged home later for their tea… ‘What one thing? I want to know, because when I’m grown up I suppose I’ll be after it too. And if I don’t like the sound of it, I’ll think of some other thing to go after.’

‘I can go after things just as much as you.’

‘She didn’t say ladies went after it.’

Howard’s writing is sharp, her observations of character keen, and one could argue that, while the Cazalet books are not demonstrably experimental and Howard’s writerly instincts are primarily conservative, she experiments with the range and durability of domestic fiction. If a definition of art is that which puts itself on trial, Howard may be cross-examining the genre to test whether domestic can be weighty, as it was with Austen. She is trying to dismantle the ‘Women Only’ sign that her publishers have plastered on her covers. Let’s pray she gets the chance.

Comments