I can’t remember how I found Stella Gibbons’ Cold Comfort Farm, the funny book that opened wide the delightful doors of middlebrow interwar fiction. Delightful. I was excited to hear that Penguin was republishing Nightingale Wood, a later work generally regarded as not as good at CCF (but Gibbons nonetheless).

At the dour Eagles, the Withers' recently widowed daughter-in-law comes to stay. Viola, an orphan and a once-shopgirl, hates the dull house and her Victorian parents-in-law. Her sisters-in-law are old and no fun. Madge is consumed with thoughts of dogs and other sporting pursuits, and tiny Tina is concerned with her appearance and her lack of love.

Across the way is the brash Spring mansion where Viola’s Prince Charming, Victor Spring, stays when not motoring off around London. Victor’s bookish cousin Hetty is dissatisfied with the frivolity of the Spring household and can’t wait to find her own flat in Bloomsbury and read poetry full-time.

What do you get when a cast of cardboard characters are driven by desire? Light comedy. Viola wants excitement and Victor, Madge wants a dog, Tina wants the handsome young chauffeur Saxon, Mr. Withers wants to manage everyone’s money, Hetty wants to gain independence (and delve into the interesting psychology of the gloomy Eagles), Mrs. Spring wants Victor to marry Phyllis, his unofficial fiancée, a Hermit wants to sell walking sticks and cause mischief…

Nightingale Wood might not be as clever as Cold Comfort Farm, but it is a light, amusing adaptation of Cinderella which showcases Gibbons’ humor. It was as though she was required to write an airy novel, but would not go without her own wry commentary and obstinately subverting the most clichéd situations into going a little bit wrong. Her characters are never wholly likable: Viola is vague and blurry; Hetty is poetic to the point of sentimentality; Victor has fits about people missing their trains and is not really the faithful sort; Saxon is so ambitious that he becomes ruthless and manipulative and only barely able to be checked by his conscious.

Despite Nightingale Wood’s meringue consistency, its balletic fripperies, Gibbons inserts sharp comments about the times she’s writing in, the undercurrent of worry in 1938. Let’s remember the turmoil of the late ‘30s as the countries of Europe struggled to both maintain their alliances and rearm:

“For though people under forty might laugh ringingly at the shocking things heard by Mr. Spurrey about Abyssinia and the Means test, about Hitler and Mussolini, and Armaments and Fascism, about Abdication and Spain, and the Special Areas and Air Defense…”

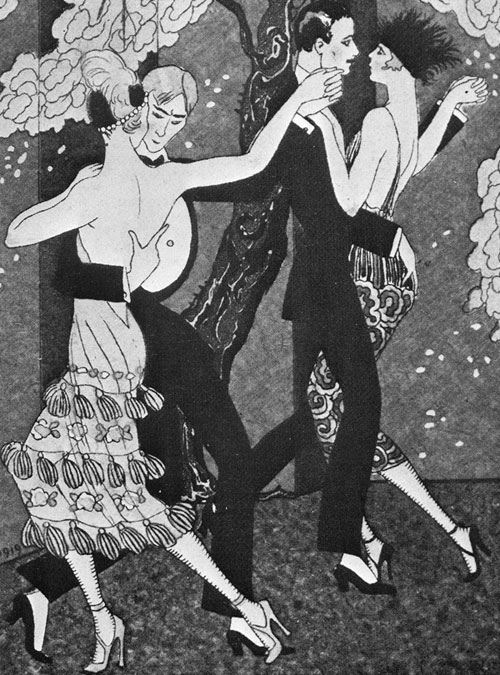

The post-Great War awareness of instant oblivion and senseless waste is present (Gibbons was 16 when WWI ended), contrasting the ecstasy of a nocturnal ball, the “milk-warm water…the beauty of the sea rolling under that green magian-light,” with “a world toppling with monster guns and violent death.” This paradox is repeated later when she writes, “The music swelled and fell as the waves of warm, moon-swayed water rolled round and round, and the dancers dreamed that life was beautiful, in a world toppling with monster guns and violent death.”

Is she acknowledging her character’s blind oblivion to their national climate, or ironically ridiculing her own construction of an alternate fairyland during a time of political and social anxiety? (This is clearly not a novel interested in social critique.) At the end of the novel when we learn “what happens next” for her characters, it is notable that there is (obviously) no talk of the war only one year away or future post-war austerities. How odd that we know what will happen and she doesn’t.

Gibbons has a special hatred for psychology, especially the German school (“Tina looked up the chapter on Fathers and Daughters in the book on feminine psychology…’What a mind the woman’s got! Just like a German.’”).

Class politics appeared more often than I expected. The author seems to know a bit (or hypothesize) about what goes on “downstairs”. The servants grumble about calling a visitor – the washerwoman who is the mother of the chauffeur/ son-in-law – madam and eventually settle on a good ol’ honest “Mrs. Caker.” The inferior classes subordinate and step off their chessboard to the Withers’ shock: “Chaffeurs, shopgirls, washerwomen…where were the Withers drifting?”

Despite the upheaval, this is no soft-shelled socialist manifesto. Communists get a bit of a jibe:

“It was a tranquil scene; it would have annoyed a Communist. Five non-productive members of the bourgeoisie sat in a room as large as a small hall, each breathing more air, warmed by more fire…In the kitchen underneath them three members of the working class swinked ignobly at getting their dinner…But perhaps this is not a very interesting way of regarding poor Mr. Wither and the rest."

This last line is telling of the author’s intent. Ms. Gibbons is informed and both aware of the uneasy political climate of her times and the ideological discussions on the table. But in the end, she, as a novelist, wants not what is correct but what is interesting.

And all her women come to happy (but not perfect) endings, and all remain cheerfully subjugated under their menfolk.

I sped through Nightingale Farm and must now forgo the nostalgia and light music for something with more overt grit: David Foster Wallace and his gargantuan monster, the Infinite Jest. We shall see.

Comments