I find it hard to disabuse myself of the notion that the biography is a secondary art. It takes the stuff of other peoples’ lives, mostly the salacious bits, and tries to make a conclusive narrative out of what is essentially fragmented. Those who can’t write their own material, become biographers. Or even worse, become writers whose sole metier is autobiography: those often shapeless (or alternately, deformed with over-significance) baggy monsters. I don’t feel that way about published journals. Journals seem fundamentally more honest. It is where self-knowledge, if possessed, gives itself away.

At an Oxfam booksale a few months ago I picked up a copy of Richard Holmes’ Footsteps , an autobiography of his experiences as the biographer of Romantic figures like Mary Wollstonecraft and Shelley. I recognized Holmes; his huge Shelley and Coleridge biographies are still well thought of. It was in reading about Holmes’ younger years as a waifish biographer, living hand-to-mouth in Europe and following the exploits of his subjects with a detective-like inclination for a story, that I began to reconsider. Holmes writes of himself as a young man possessed by his subjects, living with them as his intimate companions as he tried to stitch together what happened between Shelley and Clare Clairmont in Italy, or Mary W. in Paris during the Terror.

The author divulges his subjects’ experiences at the same time he describes his own travels: ‘In Italy my outward life took on a curious thinness and unreality that I find difficult to describe. It was almost at times as if I was physically transparent, even invisible.’

And later

‘The Shelleys’ life in Rome was, in a sense, much more real than my own. My life was a figment of my own imagination, whereas theirs was to me an absolute, historic reality – no detail of which could be invented or falsified, not even the weather.’

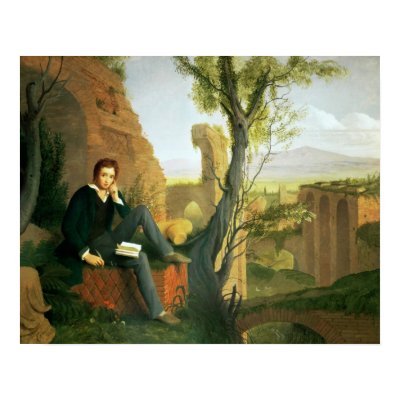

(Severn's posthumous portrait of Shelley)

Holmes is – of course – a stylishly confidant writer. There is never a pure chronology, a straight forward listing of the facts. Life is what is reported, and it is reconstructed – idealistically perhaps – from an intimate knowledge of the subject: an exhaustive knowledge of private correspondence, personal testimonies, public personae, printed ephemera, published works. It is an exercise in supposition.

Holmes describes it thus:

‘Essentially, the dramatic nature of the biography – its powers of re-creation – are fatally undermined. The literary illusion of life, the illusion that makes it so close to the novel, is temporarily or permanently weakened. In short, where the biographical narrative is least convincing its fictional powers are most reduced. Where trust is broken between biographer and subject it is also broken between reader and biographer.

‘The great appeal of biography seems to lie, in part, in its claim to a coherent and integral view of human affairs. It is based on the profoundly hopeful assumption that people really are responsible for their actions, and that there is a moral continuity between the inner and outer man. The public and private life do, in the end, make sense of each other, and the one is meaningless without the other. Its view of life is Greek: character expresses itself in action: and can be understood, if not necessarily justified.’

This has made me reconsider my relation to biography and those who write in that mode. It’s possible to have writers like Holmes who have a pure sense of their vocation, a belief in biography as a significant (and perhaps ultimately doomed) exercise. In response, I’ve got his Shelley bio on my shelf and I’ve ordered his history on the Romantics’ approach to science, The Age of Wonder.

-

Also, Neuman’s Traveller of the Century is fantastic. More to come.

At an Oxfam booksale a few months ago I picked up a copy of Richard Holmes’ Footsteps , an autobiography of his experiences as the biographer of Romantic figures like Mary Wollstonecraft and Shelley. I recognized Holmes; his huge Shelley and Coleridge biographies are still well thought of. It was in reading about Holmes’ younger years as a waifish biographer, living hand-to-mouth in Europe and following the exploits of his subjects with a detective-like inclination for a story, that I began to reconsider. Holmes writes of himself as a young man possessed by his subjects, living with them as his intimate companions as he tried to stitch together what happened between Shelley and Clare Clairmont in Italy, or Mary W. in Paris during the Terror.

The author divulges his subjects’ experiences at the same time he describes his own travels: ‘In Italy my outward life took on a curious thinness and unreality that I find difficult to describe. It was almost at times as if I was physically transparent, even invisible.’

And later

‘The Shelleys’ life in Rome was, in a sense, much more real than my own. My life was a figment of my own imagination, whereas theirs was to me an absolute, historic reality – no detail of which could be invented or falsified, not even the weather.’

(Severn's posthumous portrait of Shelley)

Holmes is – of course – a stylishly confidant writer. There is never a pure chronology, a straight forward listing of the facts. Life is what is reported, and it is reconstructed – idealistically perhaps – from an intimate knowledge of the subject: an exhaustive knowledge of private correspondence, personal testimonies, public personae, printed ephemera, published works. It is an exercise in supposition.

Holmes describes it thus:

‘Essentially, the dramatic nature of the biography – its powers of re-creation – are fatally undermined. The literary illusion of life, the illusion that makes it so close to the novel, is temporarily or permanently weakened. In short, where the biographical narrative is least convincing its fictional powers are most reduced. Where trust is broken between biographer and subject it is also broken between reader and biographer.

‘The great appeal of biography seems to lie, in part, in its claim to a coherent and integral view of human affairs. It is based on the profoundly hopeful assumption that people really are responsible for their actions, and that there is a moral continuity between the inner and outer man. The public and private life do, in the end, make sense of each other, and the one is meaningless without the other. Its view of life is Greek: character expresses itself in action: and can be understood, if not necessarily justified.’

This has made me reconsider my relation to biography and those who write in that mode. It’s possible to have writers like Holmes who have a pure sense of their vocation, a belief in biography as a significant (and perhaps ultimately doomed) exercise. In response, I’ve got his Shelley bio on my shelf and I’ve ordered his history on the Romantics’ approach to science, The Age of Wonder.

-

Also, Neuman’s Traveller of the Century is fantastic. More to come.

Comments

Shruti.