I have been traveling: to Venice, to India, to provincial England, to revolutionary France, an excellent antidote to my own grounded schedule and the envy for a friend’s recent trip to Europe. He promised a postcard.

Geoff Dyer’s Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi (2009) was recommended by several coworkers. The book is a composite of two sections: the first being the experiences of Jeff Atman, a journalist in Venice for the Biennale; the second being the experiences of an unnamed narrator (who may or may not be Jeff; his surname after all, Atman, is the Hindu word for the soul) in Varanasi, India.

The novel is clever; the narration honest and real. Its tangible veracity may be a mark of Dyer’s skills as a novelist, but I couldn’t stop the feeling that all of it had been lived. I was transported to a sun-baked Venice, to the swell and hype of the art crowd, to the installations and hotels and coke parties on yachts, to India and all its disorganization, rubbish, dirt, and squalor, where next to temples and holy men, dogs eat the limbs of the deceased in the shallows of the Ganges.

The contrast between the two parts is significant. The shallow disenchantment of Jeff the journalist and his life of bellinis, vanity, and pleasure-chasing, is answered by the narrator in Venice who does not leave after finishing his piece, but stays on to gradually renounce desire and experience some enlightenment. I can’t say that I’m the biggest fan of the goal to renounce desire and connection. Both desire and connection seem to me both deeply human, an affirmation of one’s place in the world. To escape that and to shrug it off seems like a coping mechanism, just as walking out on an argument or disagreement is not a true resolution.

That said I enjoyed Venice, Varanasi immensely. I split up its reading over several days at the bookstore which was a disservice. Beyond its cleverness and its accurate post-modern world-weariness, Dyer succeeds at avoiding the romanticizing of the foreign, no mean feat in the age of memoirs of Tuscan villa restoration and Eat, Pray, Love.

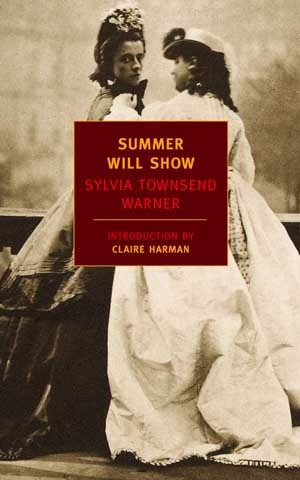

Second, I read Sophia Townsend Warner’s Summer Will Show (1936), the story of a young, rich, self-possessed English woman who travels to Paris following the death of her children to confront her husband, in Paris with his mistress. Sophia Willoughby arrives in Paris at the start of the 1848 revolution, and she becomes involved by forming a passionate attachment to her husband’s mistress, Minna Lemuel, a Bohemian storytelling Jewess whose friends are revolutionaries.

The novel turns several expectations on its head. The bereaved parent does not fall apart in grief, but is freed by the death of her children from her position as wife, mother, and mistress of an estate. Sophia does not go to Paris to confront Frederick’s infidelity, but falls under Minna’s spell and the two set up house entirely without Frederick.

Summer Will Show has superb characterization; Sophia Willoughby is one of the most fully formed characters I have encountered in a while. She is truly consistent, deeply realized, and capable of believable growth throughout the novel.

I enjoyed Warner’s beautifully written and organic novel Lolly Willowes, but Summer Will Show has much more at stake. It is less solitary, more communal, more political, more historical, more dramatic. Another incarnation of her capable, independent heroine. Sensitively realized, it has the capability to become a knock-out film or play.

Still in the nineteenth century, I am currently under the spell of Charles Dickens and Little Dorrit, both the book and the miniseries…

Comments